By Ted Lipien

Originally posted on November 13, 2020 and last edited for formatting changes on February 18, 2021.

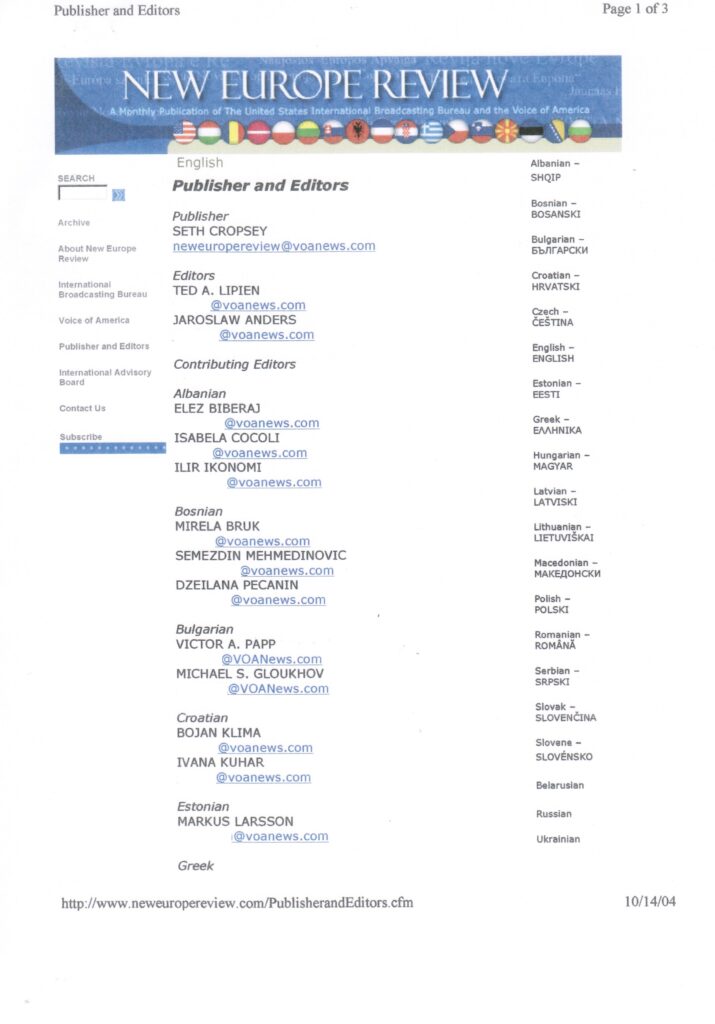

In 2004, foreign language broadcasters in the Voice of America (VOA) Eurasia Division in Washington, DC, launched a monthly multimedia, multilingual online journal The New Europe Review, which had in one of its first issues an article by Senator Joseph Biden (D-DE) on the relationship between the United States and Europe. Senator Biden was at the time ranking member of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Many foreign policy and public diplomacy issues analyzed in his commentary, including his sharp criticism of President George W. Bush’s approach to transatlantic relations, were remarkably similar to how some of the same issues are discussed today by American politicians and media. His commentary was titled “Let’s Grow Up and Start Talking: Senator Joseph Biden on U.S. Foreign Policy and Transatlantic Relations.”

In his criticism of President Bush, Senator Biden said Bush “will be judged harshly by history, it will not be because of the mistakes he has made but because the opportunities he has squandered.” Biden asserted in his article that after 9/11 “instead of uniting the world, we divided the world with our rhetoric.” There was no hit in Biden’s commentary of President Barack Obama’s future “Reset” with Russia initiative and the reneging on U.S. missile defense shield promises to NATO allies, Poland and Czech Republic. Biden as vice president did not embrace the “Reset” with Russia with the same enthusiasm as Obama did. In 2004, Biden was arguing for a better dialogue within NATO while President Obama’s later decision to remove the missile defense shield from Central Europe to appease Vladimir Putin was done without any extensive consultations with Central European NATO allies and ultimately failed to moderate Russia’s aggressive behavior. To compound the public diplomacy damage, Obama’s missile defense shield removal was announced exactly on the anniversary of the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland, a public diplomacy blunder which I wrote about and even tried to warn the White House ahead of time. As vice president, Biden did not appear to be in favor of appeasing Putin. He traveled to Central and Eastern Europe in October 2009 to allay concerns from Poland and the Czech Republic about Washington’s missile defense shield decision.

In his 2004 commentary on transatlantic relations, Senator Biden did not pay a lot of attention to Russia, and none to China. Biden and some of the other political leaders and experts we interviewed in 2004 focused on the growing differences between the European Union and the United States over Iraq, blaming the Bush administration but also to some degree the nations in Europe for not dealing more effectively with the threat from rogue leaders like Saddam Hussein and from international terrorism. Biden argued that President Bush and his neo-conservative advisors adopted a dangerous doctrine based on preemption by responding with force to any perceived threat, which, he said scared both him and the Europeans, while the Europeans, according to him, concluded that the only way to act under any circumstances was with total consensus. In his view, neither approach was completely appropriate in dealing with Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Biden concluded that what the Americans and the Europeans have to do is “to acknowledge two things: success in Iraq is in the interest of all of us, and the fight against tenor will continue.”

You have fallen in love with the notion of international institutions to the same extent that this administration has fallen in love with unilateral action. And I would respectfully suggest that just as with our failure to understand our role as the world‘s sole superpower, your all-consuming interest in the unification of Europe forced you to take your eyes off the ball in terms of the rest of the world.

Senator Joseph Biden (D-DE), remarks at the Washington conference on “Europe and the US after EU Enlargement,” organized in March 2004 by the European Union Center at the University of Michigan and the William Davidson Institute. Voice of america’s “the New Europe review,” 2004.

Senator Biden said in 2004 that he believed the United States should not have gone to war with Iraq based on the existence of weapons of mass destruction. He said that he believed that the U.S. had the right to go to war not on preemption, but enforcement. While criticizing the foreign policy rhetoric of the Bush administration, Biden was also suggesting that European NATO members should increase their military spending to even as much as 3 or 4 percent of GDP, a somewhat unrealistic goal that President Trump was also unable to achieve.

Articles by other prominent American and European leaders and foreign policy experts published 2004 in The New Europe Review also offer interesting insights on America’s role as a superpower facing foreign policy and military choices between acting alone or in cooperation with its allies.

Some of the Central European leaders and experts we interviewed for our online journal issued warnings about Russia, which the Obama White House later initially ignored. President of Latvia Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga told The New Europe Review that “if the European Union is going to be serious about itself, then it must take an absolutely iron-clad and principled stand in its relations with Russia.” Born in Latvia before World War II, she spent her early life as a refugee and immigrant in Canada and returned to her home country after a 54-year absence when it regained independence from the Soviet Union.

Poland’s future foreign minister Radek Sikorski said in 2004 that “Only by speaking to tyrants with one voice, and by backing our words with our considerable resources, can we deny them the opportunities to play countries against one another.” He also praised America’s leadership during the Cold War and stressed the need for more public diplomacy.

Thanks to U.S. official and unofficial support for the dissident movements in our countries, alternative leaders could formulate their programs. In short, we strove for becoming like the West because we were convinced that it was more moral and that it would welcome us, not because it was better armed.

Radek Sikorski, a former deputy minister of foreign affairs and former deputy minister of defense of Poland, Executive Director of the New Atlantic Initiative at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, in voice of america’s The New Europe Review, 2004

Senator Chuck Hagel (R-NE) told The New Europe Review in television interview in 2004 that “Something that has been eliminated from American foreign policy in the last 15 years is the emphasis on public diplomacy, and that has hurt America terribly.”

We are at the lowest level of international public trust in our motives and in our purpose since any time before World War II. That is partly a result of having discontinued our public diplomatic efforts to reach out to the rest of the world and make other peoples our partners. Our future is woven into a global fabric. No nation can disconnect from the rest of the world, especially not the United States.

Chuck Hagel (R), senior U.S. Senator from Nebraska and member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. interview to Jela Jevremovic from the Voice of America’s Serbian service for “the New Europe Review,” 2004

Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, former National Security Advisor to President Carter, was asked by The New Europe Review in 2004 how the West should respond to the reawakening of the Islamic world and gave this answer:

First of all, by respecting the dignity of the Muslims. You cannot deal with a very volatile, occasionally very passionate, religiously deeply committed population by essentially treating the region in a semi-colonial, imperial fashion. We have to realize that that kind of attitude, that kind of policy, has seen its day. It is in the past. It is history. It is not the future. And if we are nor careful, if we are politically not sensitive, if we try to act largely on the basis of force, we will galvanize that enormous population against us.

dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, former national security advisor to president jimmy carter, interview with “the New Europe review,” 2004

In another interview, Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski advised the Bush administration and the Europeans on how they could reach a better understanding by modifying their respective positions and expectations.

The Europeans should abandon a posture in which they seem to be saying to America: “You do what we would like you to do. In effect, let us share in the decision-making, but you, Americans, carry the burdens of the execution of such decisions. That’s a mirror image — a negative mirror image — of the posture of many people in the Bush administration towards Europe which is: “We make the decisions, but the Europeans share in the burdens.” If we were serious about a transatlantic dialogue – and particularly a serious strategic dialogue, which I think is needed both the U.S. and Europe have to approach this issue from the same standpoint, namely, if there is going to be sharing of decisions, there has to be a real sharing of the burdens.

Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, interview with Voice of america and “the New Europe review” editor Jaroslaw Anders, November 2004

One of The New Europe Review articles which impressed me the most was based on a VOA Eurasia Division on camera interview with the Grand Mufti of Sarajevo, Mustafa Cerić. He was at the time the religious leader of one of the largest Islamic communities in Europe — the Muslims of Bosnia — and a recipient of the UNESCO Felix Houphouet-Boigny Peace Prize in recognition of his furthering of inter-faith dialogue, tolerance and peace. The interview was conducted toward the end of 2004 for the issue of The New Europe Review online journal which focused on Islam in Europe. VOA Eurasia Division language services used parts of the interview in their TV programs even before it was posted online. Mustafa Cerić comments for The New Europe Review were also picked up and widely distributed throughout the region by the Croatian News Agency with attribution given to VOA.

I think that Muslims were not aware that someone sitting in a cave in Afghanistan could say: ‘I did this on behalf of all of you, and all of you must bear the consequences, even if other Muslims, in Europe and in the West in general, had nothing to do with it.’…if I had the power, I would forbid Muslims to use the word ‘Islam’ for a hundred years. Only after one hundred years would ‘Islam’ have any meaning again. Well, as I do not have the power, it is certain that Muslims will continue to use the word wherever and whenever they want.

Grand Mufti of Sarajevo, Mustafa Cerić in october 2004 interview for Voice of america’s “the New Europe review”

The best writing in English in The New Europe Review is found in the essay, “Memory and Forgetting,” by a British novelist and poet William Palmer, the author of the 1990 novel “The Good Republic” about the victims in a Baltic nation of two totalitarianism, Nazi Germany and Communist Russia, at different times allies and enemies but both oppressors of their smaller neighbors.

When we launched The New Europe Review in spring and summer of 2004, I was in charge of the VOA Eurasia Division whose journalists worked together to create a unique online platform in multiple languages for conducting a transatlantic dialogue. A supporter of our journal was former Czech President and former dissident Václav Havel whom I had asked to join our board of international advisors.

In April 2004, The New Europe Review interviewed Professor Bronisław Geremek, former member of the democratic opposition in Poland, Solidarity advisor and foreign minister (1997-2000). We asked him whether he agreed with some of the neo-conservatives in the Bush administration who saw an emerging division between “new” and “old” Europe. Geremek answered that promoting such a division would be wrong, but he agreed that for formerly communist states whose independence had been called into question by powerful neighbors and who experienced totalitarian dictatorship in recent memory “The question of security has much more significance for them than for the old members of the European Union.

New Europe Review: Some time ago U.S. secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld sparked a controversy by suggesting that there is “old” and “new” Europe. The new Europe – formerly communist states of the Central and Eastern part of the continent were supposed to feel a special bond with the United States and be free of anti- American reflexes so evident in Western Europe. Do you think such a distinction is justifiable, and if so, what are its historical reasons?

Professor Bronislaw Geremek: First of all, let me distance myself from Donald Rumsfeld’s statement. We are living through a moment when, for the first time in history, a united Europe seems really possible. It is possible precisely because the Union is joined by former communist states. This is not the time to introduce new divisions. On the contrary, America should expect – as it did in the past — that Europe will continue to unify and it will become an important, strategic partner for the United States.

Interview with former polish foreign minister bronisław geremek for “the New Europe Review,” april 2004

For our project of getting together American and European experts we received a small budget of several thousand dollars from Seth Cropsey, director of the International Broadcasting Bureau (IBB) in VOA’s parent federal agency, the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG). [In 2018, the Broadcasting Board of Governors was renamed the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM).] I retired two years later as acting VOA associate director and The New Europe Review was discontinued. In January 2013, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton told the House Foreign Affairs Committee that the U.S. international media outreach was “practically defunct.”

Our Broadcasting Board of Governors is practically defunct in terms of its capacity to tell a message around the world. So we’re abdicating the ideological arena and we need to get back into it. We have the best values. We have the best narrative. Most people in the world just want to have a good decent life that is supported by a good decent job and raise their families and we’re letting the Jihadist narrative fill a void. We have to get in there and compete and we can do it successfully.”

Secretary of state Hillary Clinton testifying before the house committee on foreign affairs, january 2013

Link: https://bbgwatch.com/bbgwatch/senator-biden-and-other-leaders-on-transatlantic-relations-voas-new-europe-review-2004/

Let’s Grow Up and Start Talking: Senator Joseph Biden on U.S. Foreign Policy and Transatlantic Relations

Senator Joseph Biden, Democrat from Delaware, is a ranking member of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The following are excerpts from his remarks at the Washington conference on “Europe and the US after EU Enlargement,” organized in March 2004 by the European Union Center at the University of Michigan and the William Davidson Institute.

There have been so many changes during the last 12 years, which we have not fully digested and comprehended yet, that it is not at all surprising we do not have it right on either side of the Atlantic. The entire structure of the world has collapsed when the Wall came down. We went from two superpowers to a single superpower. What Europeans do not understand is that my public is not at all comfortable wearing the superpower jacket The folks in my home state do not say, “Thank God we are the world superpower and everybody looks to us to blame us or to ask us to intervene.” Nobody in my state is happy that Joe Biden, along with Madeleine Albright, pushed the former president of the United States to use force in the Balkans. Nobody said it was a great idea to send American forces into Bosnia or Kosovo. Americans are not crazy about that status. The only thing they would like less than being the worId’s sole superpower is someone else being the world’s sole superpower. But it is not something we are comfortable with.

When the Wall came down, it came down at the very time when the single most important event in European history was occurring. You are actually doing something that Adenauer dreamed about. You are engaged — full-throttle — in the unification of Europe. It caused you to be totally preoccupied with your own problems and opportunities. You have fallen in love with the notion of international institutions to the same extent that this administration has fallen in love with unilateral action. And I would respectfully suggest that just as with our failure to understand our role as the world‘s sole superpower, your all-consuming interest in the unification of Europe forced you to take your eyes off the ball in terms of the rest of the world.

And a third phenomenon happened. For the first time in human history nation states were put in the position where they felt that a non-aligned, totally stateless group of actors, taking advantage of technology and the possibility of weapons of mass destruction, could inflict damage upon them that heretofore could only be inflicted by another nation state. It threw into question the whole notion we have been operating on since the Treaty of Westphalia: that you only have a right to strike another nation if you are in imminent danger, and that the way you prevented that was through deterrence. In the United States of America many in the Democratic Party, and many others, concluded that we can still deter any attack on us by our might, by the assertion of our power. In fact, that is not true. It still works very well for nation states, but it does not work well for stateless actors. So we began a debate about whether there was an intermediate doctrine that should be adopted.

The President of the United States, faced with what was a defining moment in American history at 9/11, had a ready-made wholly thought-out and fundamentally flawed, in my view, doctrine presented to him by a group of patriotic, brilliant, and thoughtful Americans (I mean it sincerely) — the neoconservative movement. At the root of that doctrine was the concept of preemption, which scared the living bejesus out of all of you, and, quite frankly, out of me. It lowered the bar from the requirement of having to have evidence of an imminent attack to virtually no standard other than: “They might hurt us.” It was a very dangerous policy to initiate and enunciate without a much clearer definition than was offered.

On the other side of the Atlantic, most of you have concluded that the only way to act under any circumstances was with total consensus, which is the way you have been operating while uniting Europe. I have been a fairly harsh critic of this administration’s foreign policy, but the truth is there were really not very many constructive alternatives offered by Europe for how to proceed with a man — whether he had weapons of mass destruction or not — who was in violation of every UN resolution that he signed. I believed we should not go to war based on the existence of weapons of mass destruction. I believed we had the right to go to war not on preemption, but enforcement. I met with the heads of state of every one ot your countries. When I asked them what was their idea, I heard basically. “Blah, blah, blah. . . international cooperation.” Name one thing other than lifting the sanctions that was offered constructively by anyone. Name one nation that said. “Let’s screw down the sanctions, let’s tighten them.” All I heard as I traveled in Europe was, “You are killing women and children. The sanctions are oppressive.” I got that part. But how about the other part? You say international institutions are important. What value are they if the rules of the road are not enforced?

So we ended up viewing al-Qaeda and its progeny in fundamentally different ways, and also viewing Iraq in fundamentally different ways. I happen to think that you were more right than we were about Iraq. Not about whether or not we should have tightened down the sanctions and made more demands and enforced, if need be, the commitments that Saddam Hussein made, but about the utility of moving into Iraq without international consensus. We did not need anybody to defeat Saddam Hussein We all know the numbers — our military budget exceeds that of every other nation in the world combined — and my colleagues in the White House believe that that translates into a policy. It does not. It is just an assertion of fact. It is one tool in the international toolbox that a great state possesses. But this is the only tool this administration believes is in its toolbox, as in that old expression: “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” This administration is myopic about the utility, the value and the capability of force in altering events in the world.

The reason I am not despairing about this, I think, serious crisis in trans-Atlantic relations that exist now is because I think that even if our values have diverged on the margins, our interests at the moments are exactly the same. I think, if George Bush will be judged harshly by history, it will not be because of the mistakes he has made but because the opportunities he has squandered. 9/11 presented us with an opportunity, for the first time in my lifetime, for one nation state to be the benefit of every other nation state. And instead of uniting the world, we divided the world with our rhetoric. And the French — and I had a long talk with Mr. Chirac, and Mr Schroeder and others — in one sense understandably took advantage or Mr. Bush’s inept manner of handling some of our relations. It worked very well for the reelection of Mr. Schroeder and for the elevation of Mr. Chirac.

But now have a new opportunity. It is clear what the outlines of the solution are to begin to rebuild our relationships, and they start in Iraq. It is not because Iraq is the center of terror, but because it is the place where we have a common interest. No matter how badly you think we screwed it up, it is very much in our common interest to get it right. Besides, it seems to me that in combating international terror there is an overwhelming need to increase our coordinated capacity. Let us not worry whether you are going ta have a common European defense, or whether or not the French are going to become a power on the comment, like some of my neocon friends say. Good luck! Buy some aircraft carriers. Increase the percentage of your GDP you spend on defense to 3 or 4 percent. I am all for it. But what matters now is whether we can put everything else aside. We can fight about the death penalty and trade agreements later. What we have to do now is to acknowledge two things: success in Iraq is in the interest of all of us, and the fight against tenor will continue. If tomorrow Iraq became which it will not — a liberal democracy — does anyone in this room think it will be the end of terror in our countries? An conversely, if we eliminate all terror, does anybody think we have solved the problem of Iraq? Let us start talking to one another. Let us grow up and focus on what we all know we have to do. In my view, that has to start with my president and my country. But l hope if he finds the wisdom to do it, you will have the grace to accept it.

Some of Senator Biden’s staffers who were opposed to the VOA’s New Europe Review project may have seen it as an attempt to save some of our East European language services at the expense of Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty after VOA stopped direct radio broadcasts in many of the Central European languages in 2004. However, I consulted with RFE/RL President Tom Dine on this project and received a promise of his support. We also discussed the possibility of getting some of RFE/RL journalists to write for or produced programs for the online journal. I knew and respected Tom Dine having previously served in Prague, the Czech Republic as regional BBG marketing director supporting both VOA and RFE/RL. My idea of preserving the impact and positions of some of the highly experienced and talented VOA journalists who worked in the Eurasia Division was to create multimedia content for sharing with local radio and television networks, as well as with newspapers and magazines. The New Europe Review was made available to anyone by electronic subscription. We targeted universities, think-tanks, television and radio stations, government offices, and major newspapers and news magazines. The journal also had it own website where its television, radio and text content could be viewed, heard, read and downloaded. Interviews were transcribed in many languages making them easy to read and republish. Our Internet editor was a young employee of the VOA Bosnian Service Dino Vatric who sadly lost his life later in a boating accident. Multimedia editors were: Valer Gergely, Adrian Karmazyn, Alan Mlatisuma, Ivica Puljic, William Skundrich and Slobodan Svrzo. Andrea Tadic and Anna Terterian were in charge of media relations. All of them were experienced broadcasters who spoke multiple languages. We received administrative assistance from Linda Atman and Cecilia Simms.

In addition to promoting a transatlantic dialogue, The New Europe Review, as we discovered, also facilitated a dialogue on transatlantic and European issues among the Europeans themselves, especially among government and media leaders in the Balkans and in East-Central Europe. The response to the journal from media outlets, as well as key political figures and experts in the region, was overwhelmingly positive. They welcomed the idea of having a serious dialogue with American politicians and experts. Some of the best VOA journalists working in the Eurasia Division were also excited about a new multimedia project which could allow them to have a significant impact in the region. By 2004, some of the foreign language services in the Eurasia Division had very few journalists left, in some services only one or two. They could no longer produce regular TV or radio broadcasts, but they were able to conduct high-impact television interviews and post articles on the web in many languages.

Most members of the Broadcasting Board of Governors, who no longer saw Russia as a strategic adversary, wanted VOA’s Central European services eliminated and would later try to cut VOA radio and television broadcasting to Russia shortly before Russia invaded parts of the territory of Georgia in 2008. Reasons of a low-level staffer in Senator Biden’s office for opposing the New Europe Review initiative were never made clear, but he may have been part of a bureaucratic struggle for resources among various Washington entities competing for federal money. RFE/RL, as a Delaware corporation grantee of federal funding from the same agency in charge of VOA, has always enjoyed strong support from the U.S. Senator from Delaware and later Vice President Joe Biden. In 2004, his Senate staffer also may have not liked the fact that the project was supported by the then IBB director Seth Cropsey who was a Republican appointee.

After I met with Biden’s staffers and explained to them that VOA and I had full editorial control, they reluctantly agreed not to oppose the launching of The New Europe Review. They seemed surprised that I was not a bureaucrat or a political appointee but a journalist who was in charge of the VOA Polish Service during Poland’s struggle for democracy led by the Solidarity independent trade union and human rights movement. But one of Biden’s staffers was never excited about the project. The journal was quickly abandoned by my successors at the Voice of America when I retired in 2006 from my last government job as acting VOA associate director. I was later told by a VOA journalist that a manager informed her that “Senator Biden did not like The New Europe Review.” I doubt, however, that Biden personally knew anything about the project. I am quite sure he would have been upset that Vaclav Havel and other prominent supporters of The New Europe Review were not informed of the VOA management’s decision to terminate the journal. The VOA management did not even secure its domain name, NewEuropeReview.com, which was soon acquired by an unknown outside entity and used for advertising of questionable products and services. The Voice of America lost a highly-effective, low-cost tool for communicating with political and media elites in countries like Hungary and Poland and having an impact without resorting to propaganda and attempts to impose a single point of view from the United States–a practice which many post-communist societies deeply resent.

There was no chance that the journal would become a venue for propaganda from any source. The Voice of America, Jarosław Anders and I had full editorial control. We designed The New Europe Review to be strictly bipartisan in its content and in full compliance with the VOA Charter.

The same issue of the journal in 2004 with Joe Biden’s commentary on transatlantic relations also included a Voice of America television interview on the same topic conducted by Jela Jevremovic from VOA’s Serbian Service with then Senator Chuck Hagel (R-NE), a Republican member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The article with his interview was titled “We Still Need Friends: Foreign Policy for the New Century — A Republican View.” Considered a moderate Republican, Senator Hegel described some of his own disagreements with President George W. Bush’s administration. In this particular issue of The New Europe Review, we did not have an official spokesman for the Bush administration–I don’t recall that we ever did–but both Biden, and particularly Hegel, presented fairly and accurately some of the key arguments of Republican neo-conservatives.

We Still Need Friends: Foreign Policy for the New Century – A Republican View

Chuck Hagel (R) is senior U.S. Senator from Nebraska and member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He gave this interview to Jela Jevremovic from the Voice of America’s Serbian service.

JELA JEVREMOVIC: What is your vision of U.S. foreign policy for the 21st century?

CHUCK HAGEL: As we look out to this hopeful, yet complicated and dangerous century it is important to review what has worked in the last fifty years. America has been very successful. A good deal of the world has been successful in keeping a world war from breaking out. We have seen relative peace and prosperity in the world since World War II. That was not accidental.

We accomplished this mostly because after World War II the United States realized that coalitions of common interest were absolutely critical. Alliances were formed: international regimes, trade regimes, financial regimes were born. That was because the threats and challenges after World War II were common to most nations. They were not unique to the United States; they required common responses.

No nation gave up its sovereignty as a result of joining NATO, or the World Trade Organization, or the United Nations. But those coalitions brought dialogue; they brought forums to deal with problems rather than isolating countries and allowing them to become dangerous. Problem spots emerged in the last 55 years because we have allowed certain areas to become isolated. The Middle East is the perfect example. So we have to reassess our relationships, strengthen our alliances. They have not inhibited America’s power but enhanced it. Another aspect of foreign policy that gets very little attention is energy security. It is vital to the future of the world, so we have to factor it into what we are doing. Global economic leadership of the United States, continuation, strengthening trade and breaking down trade barriers – all this is absolutely fundamental to our future.

Something that has been eliminated from American foreign policy in the last 15 years is the emphasis on public diplomacy, and that has hurt America terribly. All you need to do is look at the polls on America’s standing in the world. We are at the lowest level of international public trust in our motives and in our purpose since any time before World War II. That is partly a result of having discontinued our public diplomatic efforts to reach out to the rest of the world and make other peoples our partners. Our future is woven into a global fabric. No nation can disconnect from the rest of the world, especially not the United States.

JJ: You would then disagree with the Bush doctrine that includes pre-emption, coalitions of the willing, U.S. intervention in reshaping regions like the Middle East?

CHUCK HAGEL: I have had major differences with the Bush administration regarding some parts of its foreign policy. I was critical of how we went into Iraq. I think we have found out that we cannot sustain a policy in Iraq alone, or with the so-called “coalition of the willing.” The future of Iraq will not be determined for many years. There are many uncontrollable dynamics – just as there were in Afghanistan or in Vietnam. To undertake such great ventures requires international cooperation, international legitimacy, partnership with other nations. I am hopeful that the Bush administration is moving away from a certain unilateralism that we saw in the first couple of years and toward a more traditionalist approach to foreign policy in the mode of Eisenhower, Bush senior, Reagan. This administration went to the United Nations to get a new Security Council resolution regarding Iraq. The President is asking NATO and the G-8 for more involvement of our partners there. I think this administration has learned some lessons.

JJ: Does that mean that the influence of the so-called neoconservative group that favors unilateralism is waning?

CHUCK HAGEL: I think there is no question the so-called neoconservative approach to foreign policy and world issues did dominate the Bush administration thinking early on. Whether that has diminished to the point ofchanging policy is yet to be determined. If President Bush is re-elected to a second term, he will have an opportunity to reshape, recast and redirect his foreign policy. But I think the overall neo-conservative approach to Iraq and some other issues the world and the United States have had to deal with in the last couple of years has been discredited to a good extent.

JJ: Is America safer today, having pursued neo-conservative policy?

CHUCK HAGEL: I don’t know, and we won’t know it for a while. We have decentralized terrorism in a way that we do not yet understand. It is partly because we do not yet know how deep and how wide these terrorists cell are organized around the world. There is always something to say about containment. Each situation is different and has to be dealt with differently. One of the elements of containment is to isolate the enemy in order to know where the enemy is. We are going to be dealing for many years with the unknowns of terrorism.

The good news for America is there has not been a terrorist attack on our soil since September 11, 2001. Probably most people would think that almost three years after that event we would have had another attack here. We might have an attack tomorrow and we cannot predict that. We are the most open, transparent society in the history of the world. We are reorganizing our intelligence community. We are restructuring our homeland defense. We have taken a number of measures that are making America safer. I think the more important question is whether the world is safer? Is the Middle East more stable? We won’t be able to tell that for a few more years.

JJ: Can the Middle East be stabilized without resolving the Israeli-Palestinian issue?

CHUCK HAGEL: No. There is no way the Middle East can become stable and secure until the Israeli-Palestinian issue is dealt with. You cannot separate that issue from Iraq, from any other issue in the Middle East. This is not because I say it, or someone else says it, but because the Muslims believe it, the Arabs believe it. It is part of the fabric of that part of the world. Iraq, the Palestinian-Israeli issue, Syria, Iran -they are all woven into this very complicated fabric and you have to deal with all of them, yes, specifically, but also regionally and at the same time.

Progress has to be made on parallel tracks in each of these areas.

JJ: At the NATO summit in Istanbul President Bush asked for more assistance but the Europeans only agreed to train Iraqi soldiers outside of that country.

CHUCK HAGEL: There was some good news at the NATO conference. NATO agreed to take a formal role in training the Iraqi force. That was a significant plus and a new addition to our efforts in Iraq. NATO agreed to do more in supplying and equipping not only the Polish brigade there, but also the Iraqi forces. As to new NATO involvement in the force structure, the French and the Germans said they were not going to change their position on that. But that was neither new nor surprising.

I understand the differences, the politics of this. The people of many European countries thought the invasion of Iraq was wrong. You are not going to turn that around in a year or two and make them agree to send a brigade or a battalion to Iraq. These are legitimate differences and they must be worked through. That is why we have alliances and coalitions. But NATO made a commitment to do some things for Iraq, particularly training the army and police, which are absolutely critical and essential to Iraq’s future.

JJ: But President Chirac and President Bush had another argument in Istanbul over setting a date to begin the EU ascension talks with Turkey. President Chirac immediately rebuked the United States for interfering in EU affairs. Mr. Bush repeated his view the very next day.

CHUCK HAGEL: It is not a new position for either country. The United States has made it very clear in the last few years that we strongly feel that including Turkey would be an enhancement – not just for Turkey but also for the European Union. President Chirac and other Europeans have made it clear over the years they were hesitant about Turkey for various reasons. I think you also have a personality difference here. I think Chirac and Bush just do not like each other. Personalities always play a role. But you have to be careful: personalities do not dominate relationships because at some point Mr. Bush will be gone from the stage, as well as will Mr. Chirac. The French and the Americans will have to continue not only to live and work together, but also to face some of the great challenges of our time together. After all, we have been allies even before America became a nation. Were it not for the French, America would not be a nation. I think we have to keep things in perspective. Maybe president Bush could have handled it a little quieter, a little differently. But I think Chirac’s reaction was very predictable.

JJ: Can the U.S. military sustain the current muscular and proactive foreign policy?

CHUCK HAGEL: That is the real question. I have suggested to the Congress that we need to talk about in far more detail. The mission must always match the resources. As we, the United States, continue to go around the world and make more and more force structure commitments with the smallest modern-day army we have ever had, something is going to happen. You cannot make those commitments and comply with them without the resources. Iraq is a good example. We have 141,000 people over there. We have called up our reserves, our National Guard. Over 40% of the force structure in Iraq is now made up of National Guard. We are stretching and I think breaking our force structure foundation in many ways. We are calling back up 5,600 inactive reservists. We are probably going to double or triple that number before this is over. We are extending tours of duty in Iraq. We are not letting people get out of the army when their time is up. We are holding them there, which essentially is a form of draft. I think it is a very serious issue. We are going to have a retention and recruitment

problem. We are going to have a moral problem.

I meet with a lot of our people who have just come back to Nebraska and they are not very happy. Their wives, their husbands, their employers are not very happy. They did not sign on for this. So there is going to be a significant crack in our force structure foundation, if we don’t deal with these issues. That brings me back to where we started: alliances, relationships, allies. America cannot do it all. We need friends and we need help, and we always will.

The New Europe Review also published in the same issue an interview with Dr. Francis Fukuyama, Professor of International Political Economy at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University in Washington which was recorded by Carol Castiel and Jarosław Anders for VOA’s “Press Conference USA” program. Jarosław Anders and I were co-editors of New Europe Review. Anders, a distinguished Polish American journalist and writer, recently retired from the State Department where his last position was deputy office director in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. He conducted many of the high-profile interviews and edited most of The New Europe Review articles.

Legitimacy and Power: An Interview with Francis Fukuyama

Dr. Francis Fukuyama is Professor of International Political Economy at the School ofAdvanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University in Washington. He is the author of many books,including The End of History and the Last Man. His most recent book, State Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century, discusses the phenomenon of failing states and their resulting problems such as poverty, disease, refugee crises and terrorism. Dr. Fukuyama talked with Carol Castiel and Jaroslaw Anders on VOA’s “Press Conference USA.”

CAROL CASTIEL: In your best-known book, The End of History and A Last Man, you talked about the triumph of liberalization and privatization, which usually means a diminished state. In your most recent book you argue that strong state institutions are critical in this post September 11 world. What do you mean by state building and why it is so important?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I think that there is a tendency to some semantic confusion when you talk about a large state or a strong state, because I think these terms actually refer to different things. One way of conceiving states is how ambitious they are. Do they regulate industries? Do they try to put in welfare state protections for poor people? Do they transfer income or have industrial policy? The Reagan-Thatcher revolution that began in the 1980’s was a reaction against states that try to control everything.

But there is another dimension of stateness that has to do with the competence with which the state can enforce its laws. The ideal state is one that does not try to do too much, but is strong enough to enforce its own rules in some key areas, such as the rule of law, protection of property, or individual rights.

JAROSLAW ANDERS: Dr. Fukuyama, in your book you observe that so far the record of state building is rather poor. Can you elaborate?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I pointed out that since the takeover of the Philippines in 1899 the United States has been engaged in something like 18 to 20 nation building exercises. Of those only three are unqualified successes: Japan, Germany, and South Korea. And in a certain sense those were not even state building exercises, except for the South Korean case, because Germany and Japan had very powerful states already. I would say that foreign powers cannot build strong institutions if there are no local elites that want to do it themselves. The successful “tigers” in East Asia took off with a little outside help, but the motivation came largely from their own societies. There is a fundamental distinction between reconstruction and development, which means the creation of new institutions. We can do reconstruction – in Bosnia, Kosovo, East Timor. What is much more problematic, however, is how to build a strong society that then can become a self-sustaining democracy.

CC: Dr. Fukuyama, in the book you also talk about how some efforts at institution building actually hurt developing countries by destroying their indigenous capacity. What do you mean by that?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: A friend of mine, who is a reporter for The New York Times, went to do a story in Kabul. He said that his driver earned a monthly salary that was ten times the amount paid to a minister in the Afghan government In post-conflict reconstruction you typically have people from developed countries, multilateral aid agencies, like the World Bank, donors, NGO’s, who come with First World salaries and laptop computers and suck the existing capacity out from the local institutions. Once they leave, the society is in some ways worse off than before because it has no permanent bases to meet people’s needs.

JA: I would like to return one more time to the cases of Bosnia and Kosovo. You seem to suggest that they are trapped at a certain stage of the process and cannot go any further. This seems to be a larger problem. We may create new dependencies, new protectorates, or even some kind of semi-colonial entities. In the long run that does not look like a healthy situation. What mechanisms do we have at our disposal to break out of this impasse?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: In Bosnia the International Community’s High Representative is virtually a dictator. People have compared him to a viceroy in British India. Not too long ago he dismissed for various reasons a number of democratically elected local politicians. And I think that if the international community withdrew it is not clear that Bosnia would not relapse into the situation of the mid-1990’s. Again, there is no single answer to your question. Bosnia and Kosovo have underlying ethnic tensions that have not yet been resolved. Until the local actors agree on a political settlement, you cannot safely withdraw. In Afghanistan, on the other hand, an interesting model is emerging. In my view the United States deliberately went there with a light footprint. A tot of people have criticized the administration for not pumping more resources into Afghanistan. I am not sure whether the U.S. approach is such a bad way of proceeding, because it puts the burden really on the Afghans. They need to come up with their own solutions.

CC: Dr. Fukuyama, let’s turn now to Iraq. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the U.S.-led invasion, I think there is a widespread recognition that the world cannot let Iraq become a failed state. How would you assess the U.S.-led nation building effort there to date?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I think everybody is largely in agreement that the administration really did not prepare well for this at all. They began planning just a couple of months before the war, and they went in with a lot of mistaken assumptions about how peaceful the transition would be. And so they probably tost a whole year in terms of nation-building. People need to prepare much better. You need to be cautious, in the first place, when you try to do these sorts of things, but when you decide you have to do it, you need much longer preparation.

JA: Iraq seems also to illustrate a discrepancy between two views of what actually can be done in a part of the world that lacks a democratic tradition. There are the enthusiasts, or the idealists, who believe that once oppression is removed democracy and freedom will erupt. And there are the pessimists, or cultural determinists, who say there are certain regions, certain cultures that are almost impervious to democracy. What is the right balance between these two views?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I think they both are mistaken views. You cannot just force democracy wherever you want at the point of the bayonet. It is a kind of Leninism to believe that. On the other hand, people who think like those State Department officials in General McArthur’s office in Japan, who were convinced that Japan simply could not become a democracy after 1945, are also mistaken.

Culture is important but culture changes, evolves. I think you need to balance both the determinism and political willfulness in assessing how quickly a country can develop democratic institutions.

CC: What about the phenomenon of terrorism? How can we promote long term development, and at the same time combat terrorism? Doesn’t terrorism tend to undermine that long-term process?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: One clear lesson is that if you don’t have security, you don’t have economic development. Why is Africa such a mess? Although it is not terrorism that causes those problems, we see there a high degree of political instability. You have ongoing wars in the Congo, in Rwanda, in lots of other places that have been absolute obstacles to any kind of economic development. I think this is one thing that nation-builders understand. Security comes first. Unless you have security, you don’t have any of the good things that come from roads, hospitals, and other benefits of civilian contribution. There are some creative approaches to this problem. In Afghanistan civilian nation-builders are literally in the same units with military people, to provide both security for the village from warlords, and to help provide civilian services necessary for nation-building.

JA: Dr. Fukuyama. I would like to ask you about another region of the world, which is post-communist Russia and post-communist Eastern Europe. The Western approach to social and economic reconstruction there followed two simple rules: liberalize and privatize. In your book, however, we find a warning against certain dangers of something that might be called “premature liberalization.’ What dangers are you talking about?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: If you don’t have strong state institutions to provide, among other things, rule of law, it is rather dangerous to liberalize prematurely. Just take an example of privatization. It actually takes a fair amount of government capacity to carry out a privatization, because if you don’t do it well, you end up selling businesses to cronies, or to corrupt businessmen. A lot of that has happened in Russia They did not have a state that could have overseen a clean, transparent, honest privatization of state enterprises, and a lot of it ended up in the hands of oligarchs, or the Mafia. It is one of the paradoxes of state regulation. In order to deregulate, you must have a strong state that is capable of It In order to get a small state you have to have a strong state.

CC: Dr. Fukuyama, in your publications you talk about the concept of legitimacy. What is political legitimacy, particularly with respect to the United States? How can it promote successful state-building processes?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I thing legitimacy is critical to any political project because if the country in which you are operating does not regard you as a legitimate presence, the people are going to resist you in every way they can, including violently. I think we have found out that because of the American “ownership” of the occupation of Iraq it was regarded as less legitimate than it would have been under the aegis of a broader group of nations. And legitimacy is a strange concept. It is related to substantive principles of justice but it is also very relative to the people conferring legitimacy. When the Americans went into Iraq, they said, “We don’t need the United Nations to bless this because we are helping Iraqi people to achieve liberation from a brutal dictatorship.” And that was absolutely right. On the other hand, Ayatollah Sestani would not talk to anybody but a UN representative. I think that legitimacy conferred by certain multilateral institutions is oftentimes very helpful in bringing about successful nation-building over the long run..

JA: That brings me to another subject that you touched upon recently in an article published in The National Interest. You seem to question America’s ability to be an effective and respected global leader while acting unilaterally. Is America’s

hegemony an illusion?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I think that hegemony Is absolutely clear-cut in only one dimension of power, which is military power to fight and win conventional wars. In terms of nation-building it is really not that dear. In other dimensions of power, in terms of being able to project a legitimate image, it has been deteriorating. Americans need to think about that very carefully. They are able to seriously affect other parts of the world, and people resent that, because they do not think they can hold the United States accountable. Americans say to themselves: “We are doing it for their benefit Why should they complain about it?” I think the answer is: “Well, how do we know it is really for our benefit? You say so, but we would like to hear it from someone else.” It is a dilemma that we really need to address

because the United States sometimes gets It wrong.

JA: Americans tend to say, “We are doing the right thing, and that’s enough.”

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: That’s right. And there are times when it works. For example, the United States went out on a limb and said. “We want Germany whole and free, integrated into NATO,” while other people were holding back. The Europeans also could not deal with the Balkan crisis decisively enough. It took a little bit of leadership. But when you spend on defense as much as the next 16 countries collectively, you have to be a little bit careful about the way you exercise that power, or you may set off a lot of negative reactions

CC: Dr. Fukuyama, this is a presidential election year. We often hear the criticisms you mentioned about the more unilateral approach of the United States. But is it something representative of this Republican administration, or is it simply an American phenomenon? Could that change if the Democrats come into power?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I think the approach would change, although the Bush administration reflects certain characteristics that are simply American. I think that compared with Europeans more Americans regard the United Nations as not very legitimate because it is not democratic. Americans are used to believe that the source of legitimacy is the sovereignty of a democratic people, and not some large institutions. Democrats have tended to be more sympathetic towards multilateralism, so probably a Democratic president would relate better to the Europeans and other countries. But there is a thing called ‘American exceptionalism.’ Americans tend to think that their own Institutions have a universal significance. This conviction sometimes leads to confusion of American national interests and broader Interests of mankind. This is not something that is Republican or Democratic. This is an American characteristic.

Also in the same issue of The New Europe Review was an article by Radek Sikorski who at the time was a former deputy minister of foreign affairs and former deputy minister of defense of Poland and would later become foreign minister. His article was titled “Living with a Hyperpower: Ideas on Europe and the Transatlantic Relationship.”

Living with a Hyperpower Ideas on Europe and the Transatlantic Relationship

Radek Sikorski

As a European in Washington, one is surprised by many things. One of them is being denounced as a European so much that one begins to feel like one. Another is the sense that the transatlantic link is not the exclusive geopolitical link that America has, and that it is not even a necessary link. Lastly, we Europeans have collectively become a status-quo power.

The twentieth century, with its world wars, revolutions, and slaughter, exhausted us so much –we are so pleased to have buried our own demons-that we are ready to rest and enjoy peace for a while. America, as the winner in the global struggle for mastery, should be a status-quo power par excellence. What else can you desire when you have reached the pinnacle? The odd thing is that the American will to power is not satisfied. Americans remain a revolutionary people; they are as restless, as impatient, and as ready to transform the world as they were at the time Alexis de Tocqueville first described these qualities of their collective mind. So the chances that they would respond to a challenge on their home ground with a weary wave of the hand were always small. They responded with the full force of a democracy when shaken to its foundations, and the consequences have been felt across the globe.

Let us remember that the attacks of September 11 were not acts of terrorism like dozens, even hundreds, that we have suffered in Europe. It was in fact the bloodiest foreign attack on the United States in the history of that country. More people died than at Pearl Harbor, with greater economic and political impact. Let us also keep in mind that the United States has the most powerful military, not just in the world but in history, and that 90 percent of the cost of maintaining it has to be borne irrespective of whether the country is at peace or at war. And finally, the war in Iraq was in fact the result of a broad coalition that spans both main political parties in the United States.

That is not to say that Americans are uncritical of the way the war has been prosecuted, and that they may not punish in November 2004 those they deem responsible for incompetence. But in Europe we tend to forget that the Iraq Liberation Act was passed under the previous administration, that President Clinton to this day endorses the war, and that George W. Bush’s challenger, Senator Kerry, voted for it and has made no indication of wanting to withdraw prematurely. The point is that we have seen the emergence of a new foreign policy posture, which is unlikely to change irrespective of who is at the White House in 2005.

I believe that Charles Krauthammer summed it up right at the Irving Kristol Lecture he delivered at the American Enterprise Institute earlier this year. Forget isolationism-the two oceans are no longer the protection they once were; forget

Wilsonianism with its naive aspiration to end all conflict; forget narrow “realism” that pursues power for its own sake, forget empire building, which the U.S. public has no taste for; forget the 1990’s democratic globalism as both too fuzzy and too ambitious in scope. Krauthammer proposed that the right synthesis of all these strands for a vulnerable hyperpower is “democratic realism.” We will support democracy everywhere, but we will commit blood and treasure only in places where there is a strategic necessity-meaning, places central to the larger war against the existential enemy that poses a global mortal threat to freedom.

This approach is usually labeled as „neoconservative” but it is espoused by both George W. Bush and Tony Blair — the former certainly not “neo,” and the other not a conservative. The doctrine’s central belief is that democracies are inherently more pacific and more friendly to the United States. To permanently overcome your enemy’s enmity, you have to transform him in your own image, and you have to transplant something that will grow organically – namely, democracy. If I am right, this is going to be a bipartisan doctrine of the American hyperpower. I believe the Spirit of the Age has spoken. If so, what are we, Europeans to think and do about it?

First of all, we should feel lucky that the world’s leading country should adopt such a policy. Europe is, after all, closer to the undemocratic regimes that the U.S. policy sees as its targets. Most of the economic and political migrants from the failed societies on the other side of the Mediterranean Sea come to Europe, not the United States. If the Iranian mullahs manage to put a nuclear warhead on top of a missile, that missile is more likely to have the range to reach a European capital rather than Washington. And conversely, if the Greater Middle East were to shake itself out of its torpor and join the global economy, we in Europe would be the biggest beneficiaries.

At the same time, building democracy is something we know about. Most countries of continental Europe have progressed from dictatorship to democracy within living memory. We know how crucial it is, and we know how difficult it is. I believe it is safe to say that whereas extending the promise of membership in the European Union helped to sustain democracy in Central Europe, failure to do so in the Balkans fatally undermined prospects of the region. We can create concentric circles of association with our European club to transform the internal policies of our neighbors in our image.

But in order to be a useful partner to America in its task of promoting democracy, we need to create the expectation of future dynamic success. In its Lisbon Agenda the European Union has drawn a plan supposed to make Europe the most competitive and information-rich economy in the world by 2010. But the idea that a dozen men in suits can, by virtue of their solemn announcement, make Europe competitive always seemed to me ludicrous. We should get real and do the things that actually make economies competitive and efficient smash telecom monopolies, withdraw subsidies, deregulate markets, privatize remaining state industries; in short carry out the Thatcherite/Reaganite revolution here on the continent of Europe, so that its people can enjoy the same benefits of growth and prosperity that Britain and America have had. Without addressing the pervasive European aversion to risk, in economy and beyond, without embracing creative destruction as the source of innovation and growth, we will never become competitive.

Second, Americans believe that Europe is in long-term demographic decline. It may be odd to hear this at a time when Europe has just added 70 million citizens and is actually more populous than the United States, but trends are indeed ominous. Unless something is done, we will not be able to pay for the welfare entitlements of those employed today and our continent will undergo a radical ethnic transformation. The reason for this is relatively straightforward. Whereas 100 years ago a child was an economic benefit to a family, today each child

represents a cost of over 100.000 euros. France has maintained one of the highest birthrates in Europe, and it »s probably no coincidence that each French child gives their parents generous tax concessions. We need to clone the system in the rest of Europe, as well as modify the model under which you take a financial hit unless you retire the moment you qualify for a state pension.

Third, if we want to be players, we need to reform the European military. Europe spends about a third of what the United States spends on defense and it would be a serious partner if it had a third of U.S capabilities. But we have a long way to go. We continue to maintain twenty-five general staffs, twenty-five procurement policies, twenty-five armies, air forces, and almost as many navies. If we want to be taken seriously, this has to change.

Lastly, we need a common foreign policy on those things that we agree on. Only by speaking to tyrants with one voice, and by backing our words with our considerable resources, can we deny them the opportunities to play countries against one another. More specifically, the European Union must speak with one voice at the UN Security Council. Countries that talk about European unity while jealously guarding their veto power, or even trying to acquire one, are merely stoking suspicions of responding to alleged U.S. unilateralism with a micro unilateralism of their own European response to the war in Iraq should make people think. If it is impossible to unite Europe in opposition to the United States even on something as unpopular as the war in Iraq, you can either have a united Europe that develops in harmony with the United States, or a divisive anti-American fantasy.

America can also do its part to retain allies, assuming that the high tide of imperial hubris is behind us, and that the cost in lives, treasure and reputation of the mess in Iraq has brought back a modicum of realism to American policymaking.

First, Americans should remember the lessons of their own history. There is a passage in Niall Ferguson’s Empire about the origins of the American War of Independence that struck me powerfully. Americans did not secede from Britain because of stamp duty or taxes in general, Ferguson argues. The real reason was psychological: Americans had acquired a proper pride in their own success and had had enough of being talked down to. Today, Europeans are often offended by what they hear as a patronizing tone from Washington. We may be too weak to be equal partners, but we are not so weak as to be subordinates. Mutual respect is surely not too much to ask for.

Second, remember the more recent lessons of victory in the Cold War. Ronald Reagan’s military build-up was useful in making the Soviets to admit their failure but Ronald Reagan understood that the confrontation was a moral one When I was joining the Solidarity movement as a young student I did not think “Gosh, isn’t the Tomahawk cruise missile cooler than the Soviet SS-20r No. I thought “If we had freedom of the press, if we could kick out our leaders every few years, if we had a market economy, our country could be normal, and I wouldn’t have to live inside a freak social experiment” Thanks to U.S. official and unofficial support for the dissident movements in our countries, alternative leaders could formulate their programs. In short, we strove for becoming like the West because we were convinced that it was more moral and that it would welcome us, not because it was better armed.

Today, instead of offering thousands of scholarships to Muslim women–who are our natural allies–the United States has made its visa procedures so inconvenient and even humiliating that millions of people are staying out The more foreigners know the United States from Hollywood movies rather than from contact with real Americans, the more hostile they are likely to be.

Third, Americans should be careful how they formulate their ideology. I admire and

even envy the way patriotic Americans speak about their country. But American patriotism is evolving, and after the humiliation and loss of Sptember 11, it has become less inclusive. A British friend of mine, a card-carrying member of the Washington establishment for the last twenty years, put it succinctly: “Before September 11 I felt that Washington was the headquarters of the free world, and we all had our desks in It. Today, I feel more and more like a foreigner.” Foreigners will not worship at the shrine of America. They can, on the other hand, be inspired when America portrays itself as the strongest member of a community of common values and objectives.

Listen to this voice from the depths of the Cold War: “I consider myself a servant not of your country alone, because I work for the freedom of all, but since this freedom emanates mainly from your country, I have decided to join with you, and shall continue as long as my strength lasts.” So said Colonel Ryszard Kuklinski during one of his first meetings with his American handlers in the early 1970s. He went on to supply the United States with over 40,000 pages of documents, including details of the Soviet war time command bunker, designs of the latest weapons, plans for exercises of a Soviet invasion of the West and plans to crush Solidarity and introduce martial law in Poland. He risked his life on behalf of America because America represented something bigger than itself. It would be tragic if America lost that appeal and came to be seen as just another selfish nation-state.

Fourth, America should look after Its friends. If it treats countries that are hostile, neutral and friendly the same way, it will find itself with fewer friends in the future. It helps to have ambassadors who speak local languages. It is not good policy to subject foreign ministers of friendly European countries to strip searches at the airport. Do you really need to charge $100 per visa to countries to which U.S. citizens travel freely?

Today we have an opportunity we should grasp. America is a little humbled, Europe a little more worried. It may be less than we could have hoped for, but it is the beginning of a beginning. When we start thinking about what we can do together, there is no limit to what we can achieve. Through their gruesome acts, our enemies remind us every day that we are, after all, America and Europe, but we are also Western civilization.

Radek Sikorski, a former deputy minister of foreign affairs and former deputy minister of defense of Poland, is Executive Director of the New Atlantic Initiative at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

The New Europe Review in the Voice of America Eurasia Division also interviewed in 2004 former Polish foreign minister Bronisław Geremek.

We Need to Redefine the West

Professor Bronislaw Geremek, former member of the democratic opposition in Poland, Solidarity advisor and Foreign Minister (1997 – 2000), holds the Chair of European History and Civilization of The College of Europe, an international graduate studies center with campuses in Bruges (Belgium) and in Warsaw. He gave the interview to

“The New Europe Review” in April 2004.

New Europe Review: During the six decades of the Cold War the United States encouraged European integration, assuming that a united Europe acting together would be a better economic partner and political ally. After the fall of communism American leaders continued this support. But recently things got complicated. Some speak about a crisis in the trans-Atlantic relations prompted by the war in Iraq but probably having its origin in the fall of the Berlin Wall. How serious, in your view, is this crisis, and how it may impact the process of European integration?

Professor Bronislaw Geremek: One shouldn’t underestimate the significance of this crisis. The history of Euro American interactions in the 20th century has seen many crises. There were crises of trust, crises of misunderstanding, crises resulting from different political philosophies. But eventually each of these predicaments was not only resolved but also contributed something new. Those relations were founded on a certain community of interests, and therefore it was possible to work out even the most serious disagreements. What is at issue today, however, is not only the short-term difference about the war in Iraq. After all, Europe is not unanimous in that matter, and also in America one encounters views different from those of George W. Bush’s administration. At issue are two new phenomena that need to be addressed by both partners. First, there is the threat of international terrorism, which has changed the whole context of international politics. Second, there is the new phase of European integration. We are faced with dramatic questions: Will the fight against terrorism restore the old Western community of interest embodied in close European-American relations? And does America still favor a strong, unified Europe, as it did during the 50 years of European Union? I hope answers to those questions will help us avoid a breakdown

in trans-Atlantic affairs and add a new dimension to our mutual relations.

New Europe Review: Some time ago U.S. secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld sparked a controversy by suggesting that there is “old” and “new” Europe. The new Europe – formerly communist states of the Central and Eastern part of the continent were supposed to feel a special bond with the United States and be free of anti- American reflexes so evident in Western Europe. Do you think such a distinction is justifiable, and if so, what are its historical reasons?

Professor Bronislaw Geremek: First of all, let me distance myself from Donald Rumsfeld’s statement. We are living through a moment when, for the first time in history, a united Europe seems really possible. It is possible precisely because the Union is joined by former communist states. This is not the time to introduce new divisions. On the contrary, America should expect – as it did in the past — that Europe will continue to unify and it will become an important, strategic partner for the United States.

Having said that, it is true that the formerly communist states that join the European Union bring-with them a certain political culture, a mode of political behavior that grows out of their experience. These are the countries for which totalitarian dictatorship is not a theoretical concept but a recent memory. These are also the countries whose independence had been called into question by powerful neighbors. The question of security has much more significance for them than for the old members of the European Union. Let us remember that when the EU was created the main issue was not common market but the question of war and peace. The new members join the Union convinced that the issue of war and peace, the question of security, are of fundamental importance. That explains their special interest in America’s presence in European policy. We do not want this presence for ourselves, but for the whole of Europe.

New Europe Review: The pro-American position taken by the new members has caused them some problems within the European Union. They were accused of being America’s “Trojan horse” within the EU.

Professor Bronislaw Geremek: What I have just said does not mean we have no problems with the policies of the current U.S. administration. We are aware that the UN is a weak organizations and the system created in San Francisco in 1945 is not up to the challenges of the 21st century. But we are convinced that there is no other system, and therefore we have to rely on it. We believe unilateralism should have no place in international politics. Second, the question of the Kyoto Protocols and of international solidarity in the area of environmental protection has a significant resonance in this part of the world. Let’s not forget that, apart from many other diseases, communism created an ecological disaster in Eastern and Central Europe. Hence a certain psychological sensitivity to those issues. Third, the issue of the International Criminal Court. We are worried by the American position in that matter – especially by the position of the current administration. There is an expectation in our countries that the universality and supremacy of human rights is expressed also in the functioning of the international system. Despite certain objections and concerns, the

International Criminal Court is certainly a step in the right direction. Let me conclude: We welcome the American presence in European politics, but we also have a strong sense of European identity. All of the countries we are talking about, including Poland, feel that their interests and their history binds them to Europe. We do not want to have to choose between Europe and America.

New Europe Review: Let’s go back for a moment to the question of security. Advocates of close relations between America and Europe stress that only the United States can be a guarantor of security in Central and Eastern Europe, because only the United States can project its power globally. Some Europeans answer that this view is rooted in an outdated concept of security. They point out that Russia, for example, no longer poses a military-political threat to the region, while those dangers that can come from the East – terrorism, organized crime, trafficking in goods and people, AIDS, etc. – can be better handled by the Europeans than by America.

Professor Bronislaw Geremek: There is a lot of truth to it. I wish Europe could use its superior “soft power” while acknowledging the usefulness of American “hard power,” which allows Europe avoid certain expenditures. But I don’t think the definition of security has changed so much that

the question of war and peace – which preoccupied several generations in the 20th century – has become irrelevant. There is a threat not only from former empires, like the Soviet empire and the imperial tendencies in Russian politics, but also a threat of disorder, chaos, turmoil. No wall on the European Union border can protect us from that.

New Europe Review: Some worry that this wall may solidify into a permanent new division between two worlds, two civilizations. How far, in your opinion, can Europe reach?

Are there any ultimate frontiers at which it must stop?

Professor Bronislaw Geremek: In my view, this should be the key question of Polish foreign policy: Is there a possibility of enlarging the European Union eastward, and how far? Poland should keep raising this question, and I think it has some experiences and some achievements in this respect. From the point of view of Polish interests it would be good if the border could move eastward. That was the reason Germany supported Poland’s membership. In the same way Poland should support the membership of countries with which it has had historical ties. I am talking primarily about Ukraine, a large country in Eastern Europe – one often forgets about its size – and Belarus, despite its antidemocratic, dictatorial system of government.

Should Russia be also seen as a prospective members? I wish to point to an interesting statement by President Vladimir Putin, who said two months ago that Russia has European ambitions, it belongs to Europe, but is not planning to seek admission to the European Union. Therefore there is no question of Russian membership, because Russia decided not to pose it. Russia is a large country, perhaps a Eurasian power, whose ambitions extend beyond the goals of European integration. One may wonder who is joining whom – the EU joining the Russian Federation, or the other way round. The European Union is currently developing a policy of cooperation with non-member neighbors, including the Mediterranean basin and Eastern Europe. There is a consensus that this policy should take into consideration future membership of countries like Ukraine and Belarus – of course if they ask for it.

New Europe Review: You have mentioned the EU cooperation with the countries of the Mediterranean basin. I believe you refer to the so-called Barcelona Declaration of 1995 proposing a partnership with the countries of North Africa

and the Middle East. Do you envision some kind of joint, Euro-American plan to resolve the Middle Eastern conflict?