Originally posted on December 5, 2020 and last edited for formatting changes on February 18, 2021.

By Ted Lipien

The U.S. taxpayer-funded and U.S. government-operated international radio broadcaster established in 1942 had several official and unofficial names before it became widely known as the Voice of America (VOA) shortly after the end of World War II. In 1947, the U.S. government radio station for overseas audiences was still sometimes referred to as the “Voice of the United States of America” and earlier the broadcasts were listed in official documents and program schedules under the name “America Calling Europe.” However, “Voice of America,” the name by which the station is known today, had already appeared in print in 1943, a year after the launch of the first World War II U.S. government radio program to Germany. The script of the third 1942 German-language broadcast from the United States to Europe produced fully under the control of the U.S. government in the Office of War Information (OWI)–the White House’s domestic and overseas propaganda agency during the war–was titled “Voices of America.”

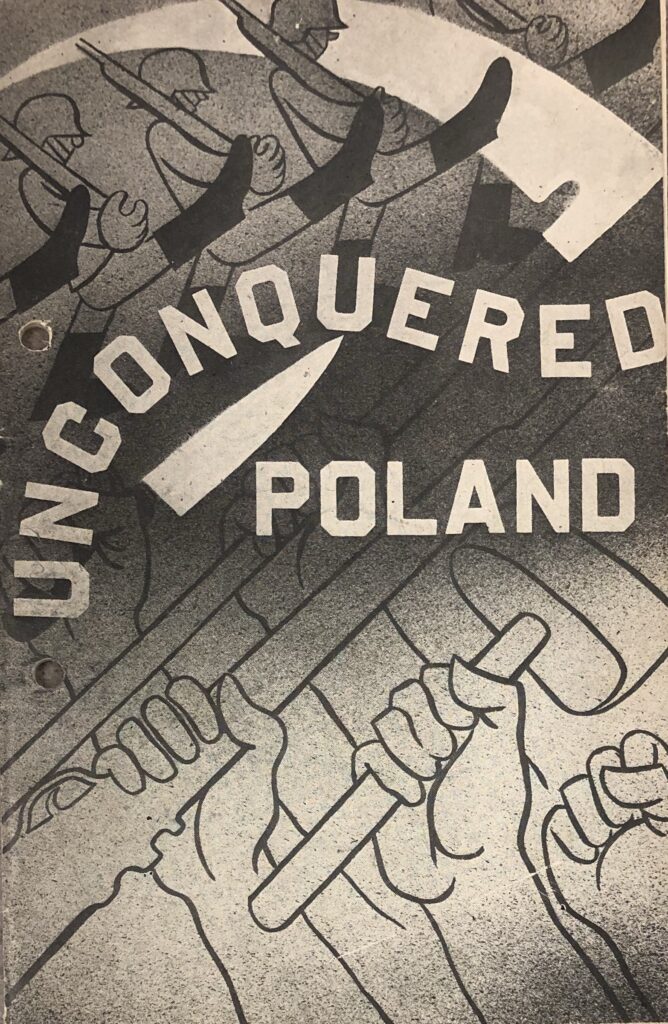

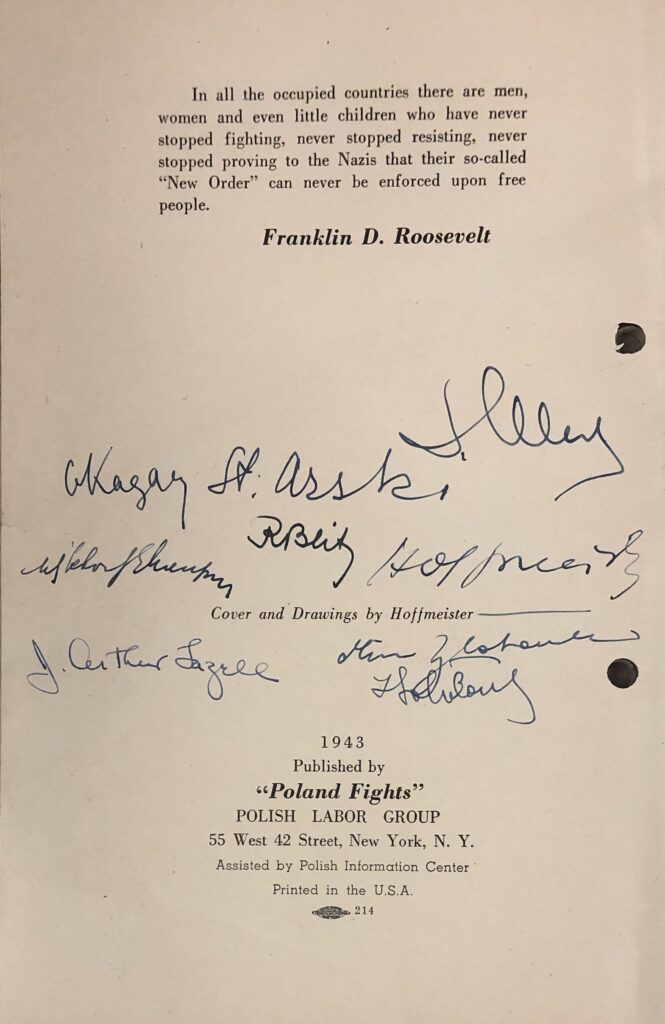

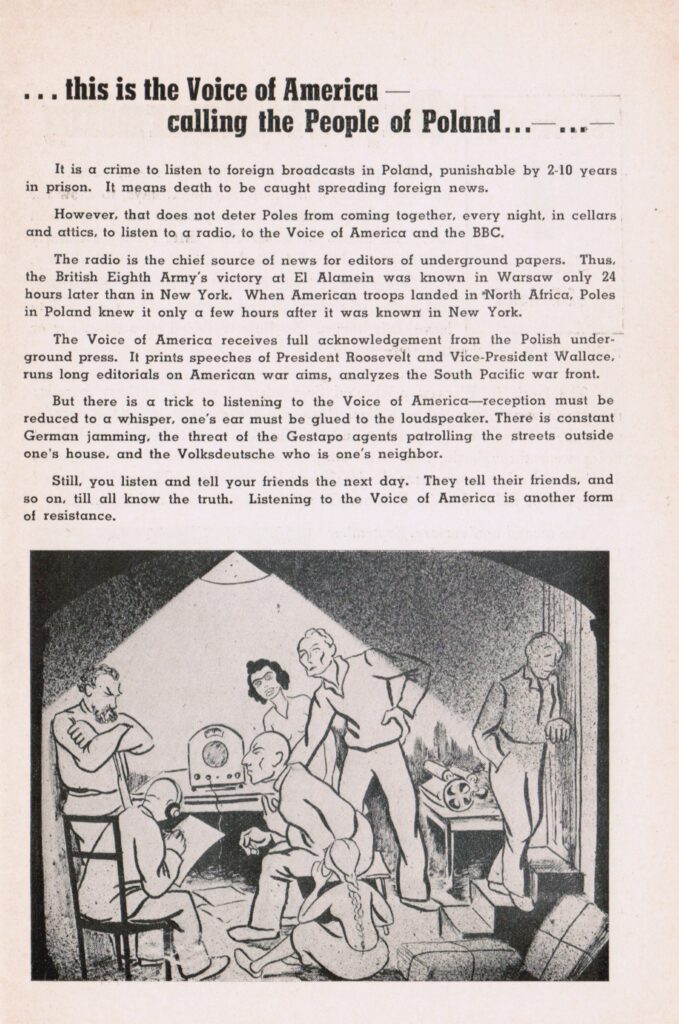

The early archival government records for the Voice of America are woefully incomplete, but the phrase “this is the Voice of America calling the people of Poland,” was used in a socialist propaganda pamphlet published in 1943 by several U.S. federal employees who edited some of the first VOA wartime radio scripts. I found the pamphlet among personnel records of one of the Office of War Information and Voice of America journalists, Mira Złotowska, stored at the National Personnel Records Center of the National Archives in St. Louis, MO. She and many other propaganda experts and radio broadcasters were non-citizen aliens employed by OWI.

Ironically, at least three of the journalists who wrote and illustrated the anti-Nazi and pro-Soviet publication, including Mira Złotowska, worked after the war for communist governments in Eastern Europe.

VOA changed from promoting Soviet propaganda and influence during World War II to countering it during the Cold War and contributing to the fall of communism, but OWI journalists who helped to spread Soviet propaganda and who supported the establishment of pro-Moscow Stalinist regimes may have been among the first to use the “Voice of America” name to describe U.S. government’s radio broadcasts to Europe during the war.

The fact that it took U.S. government officials several years from the time the first German-language broadcast went on the air in 1942 to decide on how these radio transmissions should be announced on the air and described in program schedules shows a certain degree of confusion and uncertainty during the initial period of VOA’s existence about the long term future of U.S. government-funded international broadcasting. The first German-language broadcast, which apparently aired on February 1, 1942, although there is still some uncertainty as to the exact date, used a plural noun “voices” rather than the “voice” of America. It seems that the radio broadcast to Germany in February 1942, regarded as the beginning of VOA wartime programming, did not clearly establish how the U.S. government’s international radio station should be called. It would take several years before all Voice of America programs would be consistently introduced under its current name.

Dr. Walter R. Roberts, who started his government career with the Voice of America in the World War II era Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI) which was incorporated in June 1942 into the Office of War Information, conducted research on the origins of VOA radio broadcasts and their names. He concluded that the planner of the broadcasts, Robert E. Sherwood, and their chief producer, John Houseman, wanted them to be referred to as “Voice of America,” but it appears that the name, although sometimes used by some foreign language services as they were being created in 1942, was not officially and consistently adopted until a few years later. In a few saved recordings of some of the first broadcasts, they are introduced as “The United States of America Calling the People of Europe,” or calling the people of specific countries. There was no definite name attached to these broadcasts in 1942.

Roberts presented his own recollections and his somewhat inconclusive findings about the Voice of America name in a 2011 article posted on the American Diplomacy website three years before he died in 2014 at the age of 98.[ref]Walter Roberts, “The Voice of America: Origins and Recollections II,” American Diplomacy, January 2011, http://americandiplomacy.web.unc.edu/2011/01/the-voice-of-america/.[/ref]

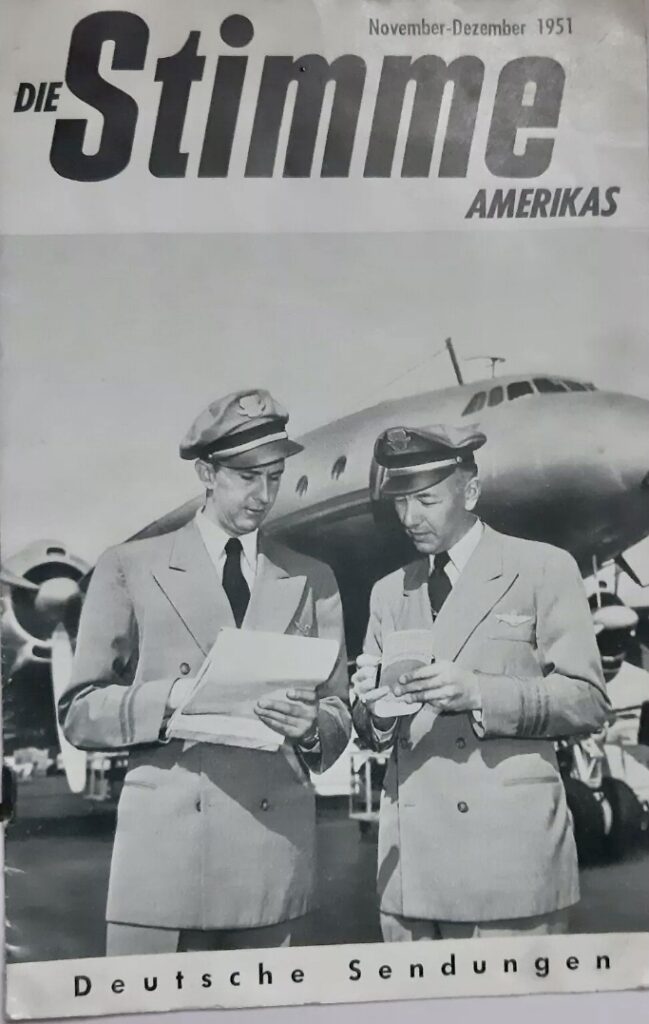

There is also an undated photo of Water Roberts posted online, which showed him in front of a microphone with the sign DIE STIMME AMERIKAS (VOICE OF AMERICA). Whether the photograph was taken during World War II or shortly after the war cannot be determined.

The COI representatives in London arranged with the BBC a daily relay system whereby not only German but also French and Italian programs would be sent by radio/telephone to London from where the BBC would transmit them (two hours later) via medium wave to Europe. It was on the basis of a BBC memorandum sent to me from the BBC Archives that I stated in my previous article that the first COI broadcast to Europe was in the German language and took place on February 1, 1942. Thanks to Kern’s research at the National Archives, I can now add a memorandum by COI Director Donovan to President Roosevelt, dated February 4, 1942 confirming the inauguration of the first COI broadcasts.

Were they Voice of America broadcasts? The aforementioned BBC memorandum contains the following sentence: “The title of the broadcasts will be ‘America Calling Europe’.” And indeed broadcasts in English as well as in French and Italian that were included in the previously mentioned VOA CD introduced themselves as follows: “This is New York. The United States of America Calling the People of Europe (English)… the People of France (French)… the People of Italy (Italian).”

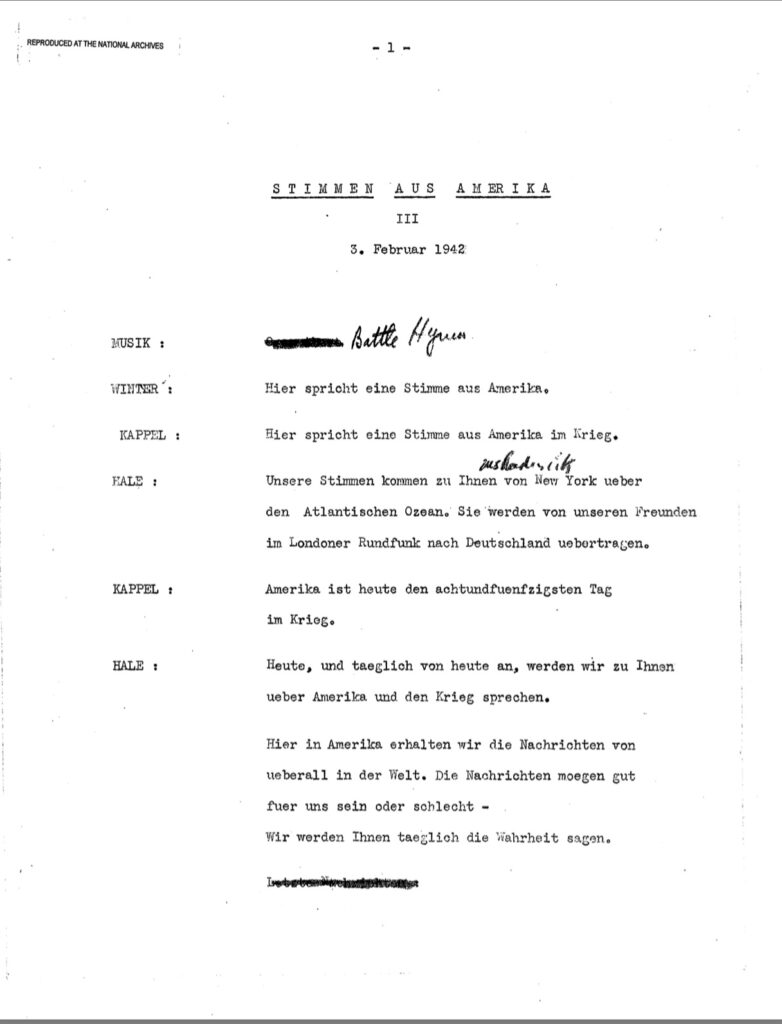

I listened to the recording of the inaugural German broadcast of February 1 at the Library of Congress and also read the script of the third German broadcast of February 3. The script is headed “Stimmen aus Amerika. III 3. Februar 1942” – “Voices from America III February 3, 1942.”

For many years, the Voice of America public relations office put out written materials showing February 25, 1942 as the date of the first VOA German-language shortwave radio broadcast. A former Voice of America journalist and manager Chris Kern concluded, however, based on his archival research that the first VOA broadcast to Germany most likely went on the air on February 1, 1942. He found in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland the script of what may be the third German-language radio program dated February 3, 1943. The script is titled STIMMEN AUS AMERICA(Voices of America) and the first line of the spoken text is: “Hier spricht eine Stimme aus Amerika” (This is a voice from America.)[ref]Chris Kern, “A Belated Correction: The Real First Broadcast of the Voice of America,” 2010. http://www.chriskern.net/essay/voaFirstBroadcast.html.[/ref]

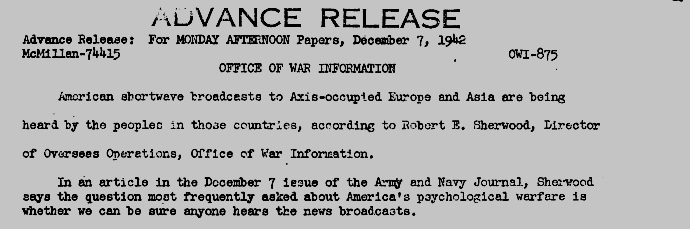

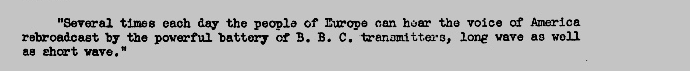

The Roosevelt administration was not very good in informing Americans about the U.S. government’s radio broadcasts for overseas audiences. One of the first, if not the first U.S. government press release about World War II U.S. shortwave programs to Europe and Asia was issued on December 7, 1942 on the first anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It took about ten months after the first German radio broadcast went on the air for the Roosevelt administration to explain to Americans in a government press release how it was responding to Nazi and Japanese propaganda.

In the press release, Robert E. Sherwood, Director of Overseas Operations in the Office of War Information, used the phrase “voice of America” but not as the official name of these transmissions. “V” in “voice” is not capitalized, either in the press release or in the magazine article to which it referred.[ref]United States. Office of War Information. [Press Release] OWI-875, December 7, 1942.[/ref] Sherwood, a Hollywood playwright who also served as President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, described what everyone then agreed were propaganda and psychological warfare operations aimed against America’s enemies. They were also designed to support underground resistance in countries under Axis occupation, as Sherwood explained in more detail in his article titled “‘Send the Word, Send the Word–Over There’: The U. S. On the Psychological Warfare Front” published in The Army and Navy Journal. Sherwood was put in charge in 1944 of coordinating American propaganda in VOA broadcasts with Soviet propaganda.

The “Voice of the United States of America” name, which was later abandoned, appeared for a few years in official documents and on photographs of VOA studio microphones. According to Walter Roberts, “During a short period in 1944, we were instructed to change the moniker ‘Voice of America’ to ‘Voice of the United States of America’,” but the longer name was still used at least for publicity purposes in the late 1940s. The mic flag station logo on this undated ACME photograph taken most likely shortly after the war had a sign in German “DIE STIMME DER VEREINIGTEN STAATEN VON AMERIKA” (The Voice of the United States of America).

“During World War II, the term ‘Voice of America’ was not well known outside our office,” Walter Roberts recalled in 2011. He wrote that “If someone had asked me then where I worked, I would have answered, ‘in the Office of War Information,’ rather than in the Voice of America.” The Congressional Record for the wartime period has many mentions and entries about the Office of War Information, including references to shortwave radio broadcasts, but the “Voice of America” name was not used by members of Congress or by American newspaper and radio reporters quoted by the legislators.

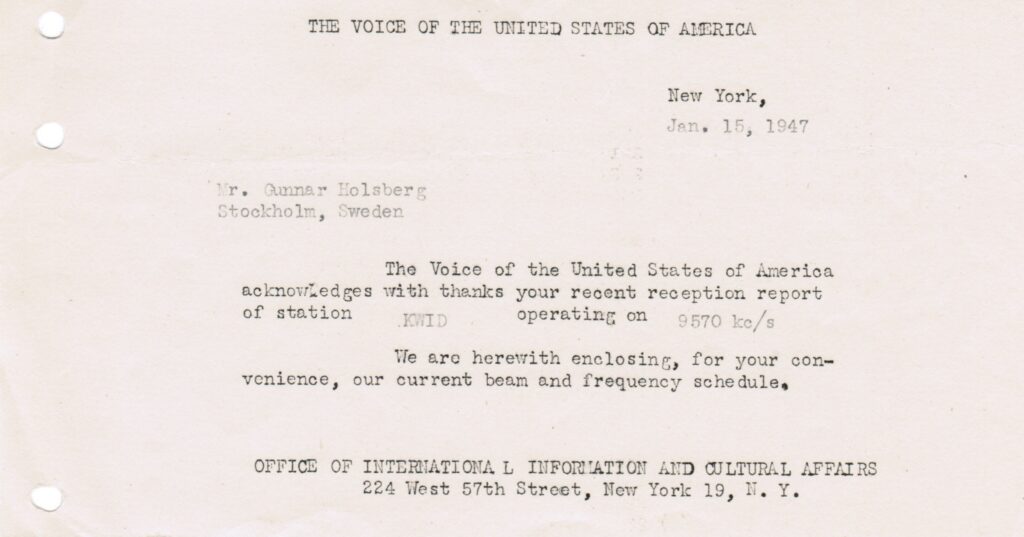

The “Voice of the United States of America” name can be also seen on a QSL note sent on January 15, 1947 to a VOA a listener in Sweden by the Office of International Information and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. State Department which at that time was in charge of VOA radio broadcasting operations in New York. From 1942 until 1954, VOA studios were located in New York at 224 West 57th Street. In 1945, President Truman abolished the Office of War Information and transferred the Voice of America to the State Department. In 1953, the Voice of America was transferred from the State Department to the newly-established United States Information Agency (USIA). VOA moved its headquarters, studios and broadcasters from New York to Washington, D.C. in 1954.

However, already in February 1946, Assistant Secretary of State William Bennett spoke at length about Voice of America broadcasts and used the name repeatedly while testifying before the House Appropriations Committee about the 1947 budget request for the State Department.[ref]United States. Congress. House. Committee on Appropriations. Department of State Appropriation Bill for 1947: Hearings Before the Subcommittee of the Committee On Appropriations, House of Representatives, Seventy-ninth Congress, Second Session, On the Department of State Appropriation Bill for 1947. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1946.[/ref]

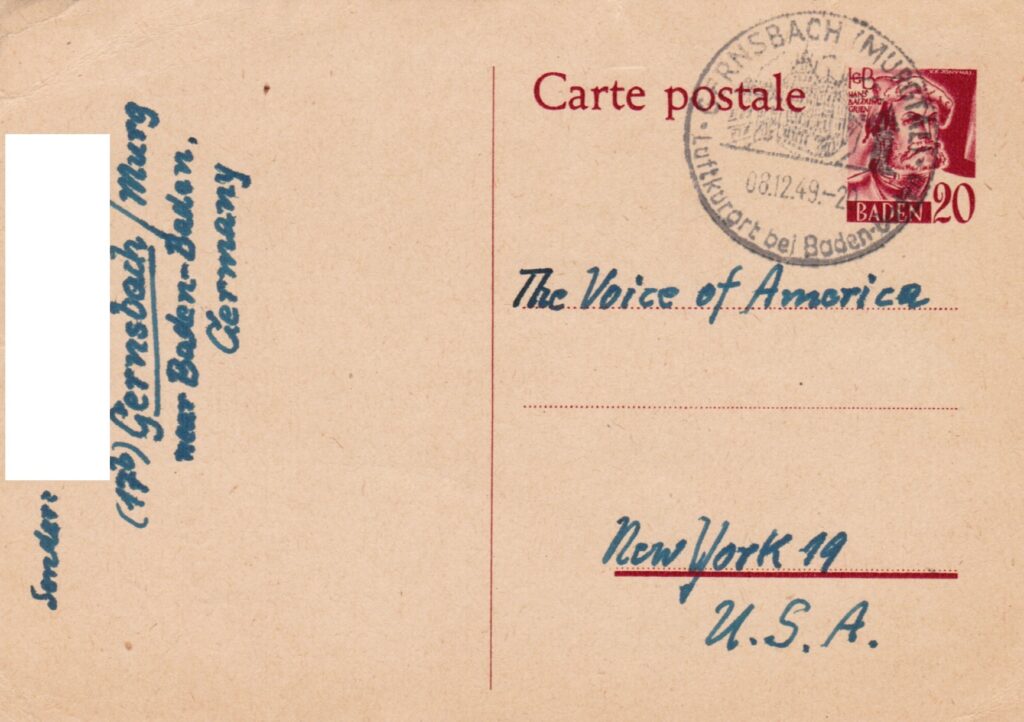

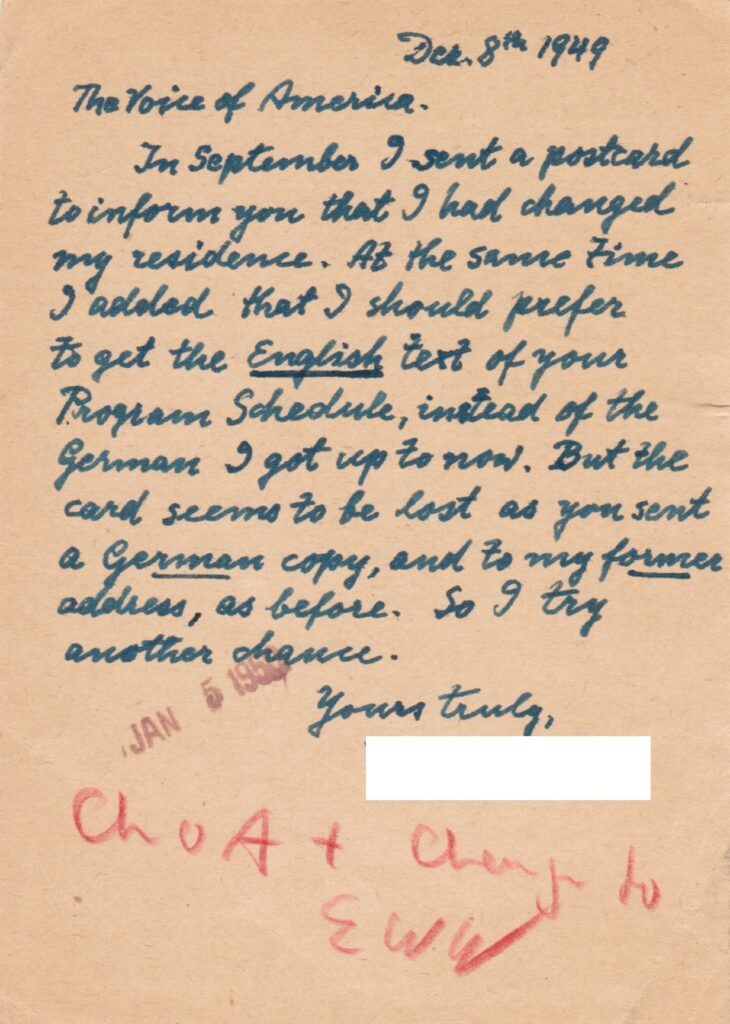

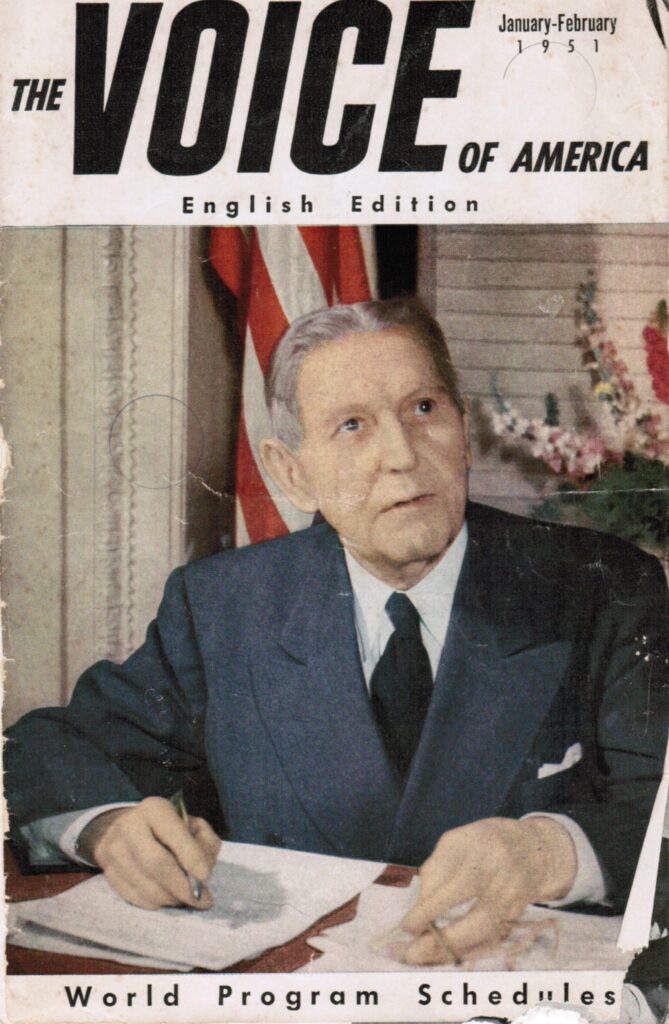

A postcard sent from Germany in 1949 to VOA headquarters in New York was addressed to Voice of America.

According to Walter Roberts, the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs requested in 1944 that the name be changed from “Voice of America” to “Voice of the United States of America” because the term America included Latin America. Roberts wrote in 2011 that “After a relative short time, we reverted to ‘Voice of America’,” but it is not clear when the change occurred or even when the “Voice of America” name was officially adopted and consistently used on the air to introduce U.S. government radio broadcasts for overseas audiences. Technical staff at the Voice of America often had to use old studio equipment because members of Congress barely tolerated VOA in its early years and refused to provide sufficient funding, but choosing signs with an old name for promotional photographs seemed unlikely unless there was still some confusion about how to use the station’s official name. The “Voice of the United States of America” sign still appeared in Russian in an official photograph published in the early 1950s.

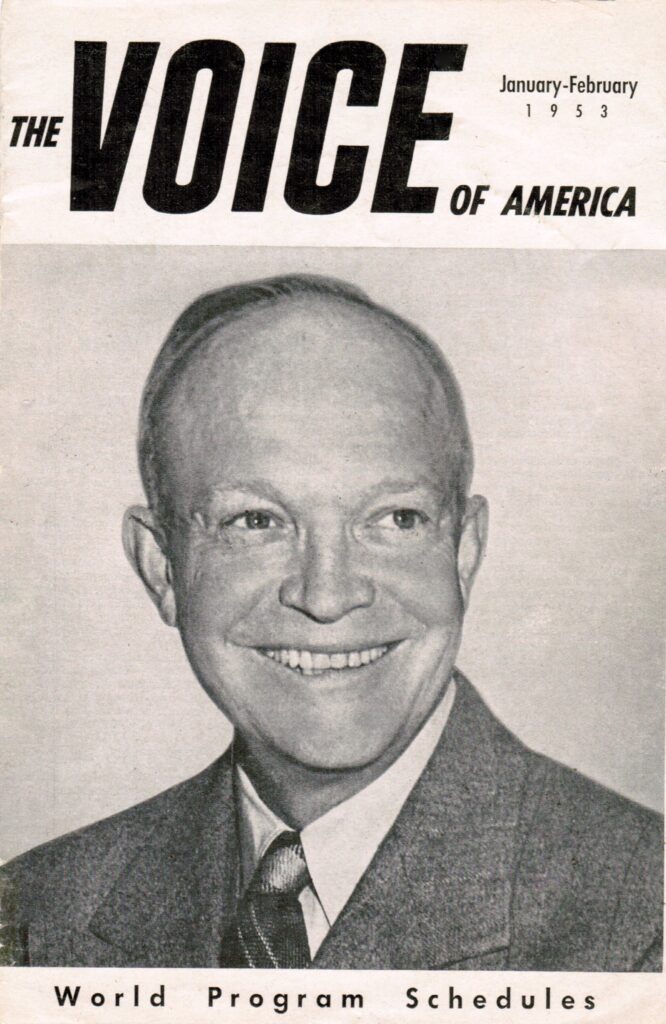

The U.S. State Department launched its public diplomacy program called “The Campaign of Truth” designed to counter Soviet propaganda using the Voice of America and the State Department’s public diplomacy programs. The “Campaign of Truth: How You Can Help” pamphlet included a photograph of a woman radio announcer holding a script in front of the microphone with the Russian sign “Voice of the United States of America.” According to a former Voice of America Russian Service director Marina Oeltjen, the woman in the photograph was Helen Zhemchuzhny Bates Yakobson (1913-2002). Yakobson had joined the Voice of America as it was being reformed and was put to work on the Russian-language program which was launched in 1947, but she was no longer working for VOA when the pamphlet was published by the State Department most likely in 1952. The Voice of America did not broadcast in Russian during World War II apparently because Roosevelt Administration officials were afraid of offending Soviet dictator Josef Stalin. The State Department pamphlet clearly referred to “Voice of America broadcasts,” but the photograph taken earlier still showed the old “Voice of the United States of America” name in Russian.

A photograph dated May 8, 1952 showed a mobile studio bus with a large Voice of America sign and a smaller “International Broadcasting Division U.S. Department of State” sign below. While by the early 1950, the official name issue for Voice of America broadcasts was resolved, its mobile studio bus shown in the 1952 photograph was a subject of some controversy during hearings in February 1953 before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the U.S. Senate Committee on Government Operations chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI). Donald R. Creed, assistant chief of the Domestic Transmitter Division of the Voice of America, testified that the mobile unit was built with an engine and springs that could not handle the weight of the equipment and the bus had no hand break. The final cost of the unit after the repairs to make it usable was slightly over $41,000 (about 400,000 in 2020 dollars), but even after extensive renovations the bus was used only twice in six months, the VOA engineer told the subcommittee because “No one wants to use it. No one wants to take it out.”

SENATOR DIRKSEN. How many times would you say it has been used since it has been completed and overhauled?

MR. CREED. Twice to my knowledge.

SENATOR DIRKSEN. Twice? You have $40,000 invested in a remote control unit, and you have used it twice?

Mr. CREED. Yes, sir.

SENATOR DIRKSON. That is not maximum efficiency by nay means; is it?

Mr. CREED. No, sir. No one wants to use it. No one wants to take it out?

SENATOR DIRKSEN. You mean they are afraid it will tip over or something?

Mr. CREED. Well, not now. They were in those days.[ref]United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Government Operations. (1953). State Department information program–Voice of America: Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, Eighty-third Congress, first session, pursuant to S. Res. 40, a resolution authorizing the Committee on Government Operations to employ temporary additional personnel and increasing the limit of expenditures. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.. Pages 40-42. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044059332916?urlappend=%3Bseq=52.[/ref]

Senator McCarthy and some other members of his committee alleged that “mere incompetence could not explain away all this waste.” But, as correctly noted by Edward Carleton Hedwick, Jr. in Policy problems in the Voice of America – 1945-1953, the hearings “failed to substantiate these charges.”[ref]Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., Policy problems of the Voice of America: 1945-1953. Master Thesis Thesis, Department of Political Sciences, University of Southern California, June 1954. 76. Also see: United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Government Operations. (1953). State Department information program–Voice of America: Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, Eighty-third Congress, first session, pursuant to S. Res. 40, a resolution authorizing the Committee on Government Operations to employ temporary additional personnel and increasing the limit of expenditures. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.., Part I, p. 8. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044059332916?urlappend=%3Bseq=19.[/ref]

Communists and Soviet sympathizers who were working for the Voice of America during World War II, including VOA’s first chief news writer and editor Howard Fast, a 1953 recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize and Communist Party USA activist, had a major influence earlier, but they were long gone from VOA by the time Senator McCarthy started his anti-communist witch hunt. The McCarthy hearings merely documented waste and incompetence within the U.S. international broadcasting entity which by then already had settled on the Voice of America as its official name.[ref]Ted Lipien, “Stalin Prize-Winning Chief Writer of Voice of America News,” Cold War Radio Museum, March 12, 2019, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalin-prize-winning-former-chief-writer-of-voice-of-america-news/.[/ref]

In addition to some uncertainty as to the origin of its name, there is also some uncertainty about the origin of Voice of America’s Yankee Doodle signature tune. Howard Fast claimed in his memoir Being Red that while working in 1943 as Voice of America’s chief news writer and news director, he had selected as a joke Yankee Doodle for VOA’s station ID tune. He also confirmed in his memoir that he used information from the Soviet Embassy and censored negative news about Soviet Russia, rejecting it as “anti-Soviet propaganda.”

I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested “Yankee Doodle” as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth, conveyed by short wave as well as by our four-hour American BBC. When I sat down to write “Good morning, this is the Voice of America,” I now has a grasp of things.[ref]Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 18-19.[/ref]

Whether Howard Fast’s claim about Yankee Doodle is true cannot be proven, but this future reporter and editor of the Communist Party USA newspaper and Stalin Peace Prize winner may have also helped to give the Voice of America name to U.S. government wartime broadcasts in English. As a master propagandist, he would have seen the need for a short and easy to remember name for the U.S. international radio station. Fast’s Office of War Information colleagues–Stefan Arski (aka Artur Salman), Mira Złotowska (aka Mira Michałowska, Mira Michal) and Adolf Hoffmeister–may have been also the ones who first started to popularize the Voice of America name in the United States and abroad. The name appeared in their socialist propaganda pamphlet which they had published privately in 1943 to target American readers.[ref]Unconquered Poland (New York: Polish Labor Group, 1943).[/ref]

Helwick concluded, citing H. Sergeant’s “Voice of the Free World” address to Inland Press Association in Chicago on February 13, 1950, which was reprinted in part in U.S. Department of State Bulletin of June 19, 1950, that the Voice of America “received its name during World War II from the common practice of using the expression ‘this is the voice of America’ as the opening and closing signature on overseas broadcasts.”[ref]Helwick, 7.[/ref]

The propaganda pamphlet, calling for radical socialism and a pro-Soviet government in post-war Poland, which included a promotional writeup about the Voice of America, was printed and distributed in the United States with the apparent blessing from U.S. government bosses of journalists working on VOA programs in the Office of War Information. Much of the information in the pamphlet about the conditions of life in Poland for the Poles under the German-Nazi occupation was true, but the authors misled Americans about accuracy, truthfulness and usefulness of Voice of America broadcasts in Polish. The German occupiers confiscated radio receivers from the Poles. Those who could listen in secret were tuning mostly to the BBC and the Polish radio station Świt which was also based in Great Britain. VOA radio broadcasts at that time contained Soviet propaganda and lies about the Poles who were executed by the Soviets or sent to the Gulag. The Poles listening during the war to Polish-language radio broadcasts produced by the U.S. government found them to be naive and were not quite sure about their name. Czesław Straszewicz, a Polish journalist based in London, did not have a very high opinion of VOA’s wartime broadcasts to Poland “whatever name they had then.”

“With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.”

I remember as if it were today when the (Warsaw) Old Town fell [to the Nazis] and our spirits sank, the Voice of America was broadcasting to the allied nations describing for listeners in Poland in a happy tone how a woman named Magda from the village Ptysie made a fool of a Gestapo man named Mueller.[ref]Czesław Straszewicz, “O Świcie,” Kultura, October, 1953, 61-62. I am indebted to Polish historian of the Voice of America’s Polish Service Jarosław Jędrzejczak for finding this reference to VOA’s wartime role.[/ref]

Of the early VOA Polish Service broadcasters and editors who were later worked for pro-Soviet governments in Eastern Europe, Mira Złotowska resigned in 1944 and and Stefan Arski resigned from the Voice of America in 1947 and became the chief anti-American propagandist for the communist regime in Poland. Adolf Hoffmeister resigned in 1945 to become briefly the ambassador to France for the Soviet-dominated government in Czechoslovakia. Hollywood actor John Houseman, who was later declared to be the first Voice of America director, was merely responsible for the production of first VOA radio programs and for hiring many of his communist friends. The person in charge of the overseas broadcasting operation was Robert E. Sherwood. Houseman was forced to resign in 1943 when high-level State Department officials refused to give him a U.S. passport for government travel abroad.[ref]Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 4, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/.[/ref] The State Department also refused to issue a U.S. passport to Howard Fast who resigned from his Voice of America chief news writer and news editor position in 1944 and became a Communist Party activist and journalist.[ref]Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 4, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/.[/ref] After leaving the White House in 1961, former President Dwight D Eisenhower briefly alluded in his memoirs Waging Peace (1965) to the Voice of America’s wartime record of propaganda collusion with Soviet Russia. He wrote that “During World War II the Office of War Information had, on two occasions in foreign broadcasts, opposed actions of President Roosevelt; it ridiculed the temporary arrangement with Admiral Darlan in North Africa and that with Marshal Badoglio in Italy.” “President Roosevelt took prompt action to stop such insubordination,” Eisenhower noted. He did not call these early broadcasts Voice of America, but his criticism was added to observations about a VOA reporter whom he accused of trying to generate negative news about his Middle East policy.[ref]Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279. Also see: Ted Lipien, “General Eisenhower accused WWII VOA of ‘insubordination’,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 14, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/general-eisenhower-accused-wwii-voa-of-insubordination/.[/ref]